Why Fake Banana Flavor Doesn't Taste Like Real Bananas

- Photo: Concentrating on Chromatography: Why Fake Banana Flavor Doesn't Taste Like Real Bananas

- Video: Concentrating on Chromatography: Why Fake Banana Flavor Doesn't Taste Like Real Bananas

🎤 Connor Johnson

Connor Johnson, a researcher from the University of Alberta, discusses his award-winning honours project analyzing the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in two banana species using headspace gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (HS-GC-MS). He completed this specific project as an undergraduate at Thompson Rivers University (TRU).

For over 60 years, commercial banana flavoring has remained unchanged—even though the fruit it's supposed to mimic changed in the 1950s. Connor's research reveals why fake banana tastes fake: the commercial banana extract contains only 3 compounds compared to 18+ in real bananas, missing critical compounds that create authentic banana flavor.

This episode covers:

- The history of banana flavoring and the myth of the Gros Michel banana

- What Connor discovered when comparing Cavendish vs. Gros Michel bananas

- The real compounds behind authentic banana flavor (hint: it's not just isoamyl acetate)

- Why headspace GC is ideal for volatile organic compound analysis

- Challenges with sample prep and instrument troubleshooting in research

- How this research could revolutionize flavor chemistry in the food industry

- The broader applications of comparing artificial flavorings to real fruits

Connor won two national conference awards for this work and shares insights into the analytical challenges of flavor chemistry, including instrument downtime, sample matrix effects, and why creating authentic synthetic flavoring is harder than it seems.

Perfect for chemistry students, flavor scientists, and anyone curious about why banana candy tastes nothing like real bananas.

Video Transcription

Why banana flavor doesn’t taste like bananas

Connor: We have to go back about a year and a half. I was working on an organic project that was unrelated, but I had a supervisor I really wanted to work with. I asked if she would supervise an honors project. She said yes and asked what I wanted to work on.

I said it would be really cool to do something with food science. Then I asked: “Why does banana flavoring not taste like bananas?” That was the original big-picture question. She’s an organic chemistry professor—Jess Allingham from TRU—and she said, “Let’s do it.”

My proposal even said I was going to try to make a banana flavoring, but first I had to figure out what was in bananas. So the first step was analysis, and that ended up becoming the whole project.

We got to the point where we found the different VOCs we could detect in banana species and in banana flavoring, and we compared them. Technically, you could make a new banana flavoring—but it’s expensive to make many different esters or alcohols, and you’d also need food-safe production conditions, which we didn’t have. So that part became more of a long-term “someone else could do it later” idea.

It became a passion project. People love the banana project. Everyone eats food, so we should know what’s in it.

David Oliva: That reminds me of banana candy. I enjoy it, but it doesn’t really taste like an actual banana.

Connor: Exactly. It resembles banana, but it doesn’t truly taste like it. Fruits do their job of “making flavor” really well. Banana candies with actual banana are hard to do—people have tried with varying success.

Comparing banana species and “the banana flavoring myth”

David Oliva: You analyzed two different banana species. What compounds did you identify, how did they differ, and what surprised you?

Connor: The most important compound—off the top of my head—is isoamyl acetate (the classic “banana candy” compound). It was the largest-abundance compound, about 30% of the profile in both.

The two bananas I analyzed were:

- Gros Michel (often discussed as the older “classic” banana)

- Cavendish (the typical grocery-store banana)

I also looked at a commercial banana flavoring (I won’t name the brand).

There’s a common idea that banana flavoring is modeled after the old banana. It’s not. That’s a myth.

A quick history note: In the 1930s, Gros Michel struggled due to Panama disease, and bananas became difficult to get. Banana flavoring became popular as a substitute—often relying heavily on isoamyl acetate because it tasted the most “banana-like.” People later started saying the flavoring was modeled after the old banana, but the overall takeaway is that the banana species are actually very similar in their flavor compounds.

There were minor differences in isoamyl acetate:

- Gros Michel: about 36%

- Cavendish: about 33%

Across both bananas, the compounds were relatively the same. If there were differences, they were often “fingerprint-level” amounts—but even small differences can affect flavor. Also, sugar content and subtle compositional differences affect how you perceive the taste. Gros Michel is often described as a dessert banana, and it’s sweeter than Cavendish.

David Oliva: So isoamyl acetate is the primary “banana flavor” compound, but other minor compounds also shape the authentic banana profile—along with sugar content?

Connor: Yes. It’s a combination of the relative amounts of compounds and the sugar content influencing perception.

Banana diversity and real-world sampling challenges

David Oliva: You mentioned different banana varieties in other regions.

Connor: There are thousands of banana species. In some regions you can find bananas with unusual colors and distinct flavor notes. We only “know” the variety that ships well—Cavendish.

For the project, sourcing Gros Michel was expensive. We imported bananas via a distributor out of Miami. Shipping was about $100, and it ended up being around $20 per banana in Canadian dollars. They also spoil quickly. If you get a chance to try a Gros Michel banana, it might not change your life—but it might.

Instrument downtime and what Connor would do differently

David Oliva: It sounds like instrument downtime impacted your data collection. If you could run the project again, how would you do it differently?

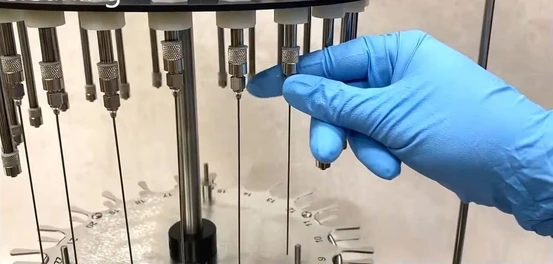

Connor: I wish I had known the issue earlier. The problem was the headspace injector needle (or something in that pathway). Some days I’d run Cavendish samples and get great peaks. The next day—same parameters—I’d get only baseline. That happened for months. People changed the column and other parts, but it ended up being the headspace needle.

If I had known sooner, I would’ve had more time to run samples and optimize parameters. My parameters worked to detect the VOCs, but I would’ve liked better separation and shorter run times so I could run more samples.

At TRU we had one GC-MS that also had to be used for classes and other work—having a dedicated instrument is a dream for many students. Luckily, it was fixed in the last few weeks before the report was due, so I got results and finalized the project.

Headspace GC-MS workflow for banana VOC profiling

David Oliva: Walk us through the headspace GC workflow, including sample prep steps, and why you chose headspace over direct injection or other methods.

Connor: The logic for headspace was: I read that the VOC profile (what you smell) is closely related to the flavor profile. There wasn’t anything directly comparing the banana species I chose using headspace. Also, early on I was still thinking about potentially creating a new flavoring and wanted to focus on VOCs.

Sample preparation (final workflow):

- Weigh out about 0.5 g banana into a headspace vial

- Mash the banana

- Add a small amount of water (about 1 mL, mainly for standardization)

- Place the vial in a warm water bath at about 50 °C for 5 minutes to help volatilize lower-boiling compounds

- Run the vial on the GC-MS using headspace injection

I don’t remember every parameter now, but the headspace oven time was not very long because I pre-volatilized it. I didn’t want to “ripen” the banana during heating, because ripening can generate unwanted VOCs. The goal was to profile what a banana actually tastes like—not a highly ripened or processed banana.

Compound identification and data handling:

- I used the NIST library/database to identify compounds (this was a qualitative study)

- I was not quantifying concentrations; I used peak area percentage (relative composition) to compare samples

David Oliva: You’re the second researcher in a row who’s talked about the value of NIST.

Connor: It’s great. It saved a lot of headache. If I could’ve made it quantitative, I would have, but that led to additional issues.

Extraction attempts and why headspace remained the core method

David Oliva: Did you use extraction techniques like SPME, and how did that impact sensitivity and reproducibility?

Connor: Before I even started analyzing by headspace, I tried to extract VOCs from the banana material. I tried:

- Steam distillation (but heating to ~100 °C effectively “ripens/cooks” the banana and alters the VOC profile)

- A small-scale CO₂ extraction concept using dry ice and warming to drive CO₂ through the sample (great idea, but bananas are dense and high-water-content; it didn’t penetrate well)

I tried many variations: changing vessel size, different sample prep, freeze drying, nitrogen freezing, drying and grinding—many methods. I couldn’t reliably extract VOCs that way. Maybe solid phase extraction or supercritical fluid extraction could work, but it wasn’t successful for me.

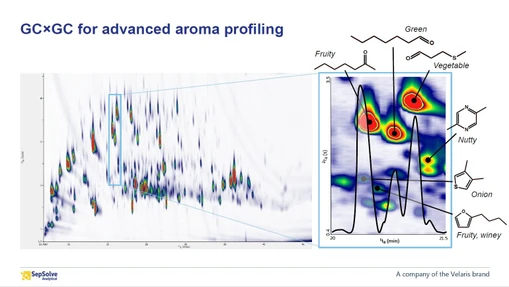

I considered SPME, but stayed with headspace to see results. Looking back—with more GC knowledge now—I wish I had run a comparison between SPME headspace and static headspace to evaluate sensitivity differences and how much analyte might be missed.

Matrix effects and detection challenges in fruit samples

David Oliva: What detection challenges did you face with the banana matrix?

Connor: Any fruit has matrix effects. Because I was working with solid fruit, it wasn’t ideal. I didn’t address matrix effects in the project, but I wish I had done something like standard addition to quantify how much signal is suppressed or altered.

At the time, I was more focused on getting detection at all than on correcting matrix effects. It’s a shortcoming I’d like to revisit in the future—maybe later in my career.

From Headspace GC to LC-MS instrument development

David Oliva: You’re now doing LC-MS instrument development. What lessons carried over from your Headspace GC work?

Connor: Being comfortable working with instruments was a big advantage. At a smaller university, I got more hands-on time than many undergrads. That comfort translated well into LC-MS work.

I can’t share details of what I’m working on now, but I’m working on a new interface. The confidence from hands-on GC experience helped me feel more comfortable with software and instrumentation. A lot of people are hesitant to approach expensive instruments, but we still need people who can work with instruments—not only analyze data.

Advice for students moving into separation science and MS

David Oliva: For undergraduates starting out—especially those transitioning between techniques—what advice would you give?

Connor: Have the initial conversation. Say:

“I really like the work you’re doing. I want to learn more about LC-MS or GC-MS or ICP-MS. I want to work with you—can you help me?”

That first email or meeting is the hardest step for many people. Showing genuine interest gets your foot in the door and can lead to longer conversations and opportunities.

Future directions and applications in flavor science

David Oliva: Anything else you’d like listeners to know?

Connor: If anyone wants to work more on the project, feel free to reach out. This kind of work is applicable to many foods: compare grape flavoring vs. grapes, cherry flavoring vs. cherries, strawberry flavoring vs. strawberries.

It could also be used for adulteration testing: checking whether a “natural flavor” is truly natural or essentially a small set of compounds. That was one takeaway—some flavorings claim additional natural flavors but may contain only a few compounds.

There’s a lot of work left in the flavor industry. If you’re interested, dig into it. If you ever think “why does this taste weird?”—there’s probably a compound behind it worth studying.

David Oliva: I was attracted to your work because it’s a question everyone has asked—bananas vs. banana flavoring. Thanks for coming on and sharing it.

Connor: Thanks for the invite. Maybe in the future I’d be happy to come back and talk about more GC work when I have a new project—or when I’m a PI.

David Oliva: Awesome. Thank you.

This text has been automatically transcribed from a video presentation using AI technology. It may contain inaccuracies and is not guaranteed to be 100% correct.

Concentrating on Chromatography Podcast

Dive into the frontiers of chromatography, mass spectrometry, and sample preparation with host David Oliva. Each episode features candid conversations with leading researchers, industry innovators, and passionate scientists who are shaping the future of analytical chemistry. From decoding PFAS detection challenges to exploring the latest in AI-assisted liquid chromatography, this show uncovers practical workflows, sustainability breakthroughs, and the real-world impact of separation science. Whether you’re a chromatographer, lab professional, or researcher you'll discover inspiring content!

You can find Concentrating on Chromatography Podcast in podcast apps:

and on YouTube channel