Introducing Headspace Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry to Undergraduate Chemistry Students from a Forensic Toxicology Perspective

J. Chem. Educ. 2026, 103, 1, 441–448: Graphical abstract

This laboratory experiment introduces undergraduate chemistry students to headspace GC–MS through a forensic toxicology framework. Students analyze common volatile compounds such as ethanol, isopropanol, acetone, and 1,1-difluoroethane while learning key concepts in gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, calibration, and data evaluation.

Participants prepare calibrators and controls, quantify ethanol, and assess qualitative analytes in a simulated vitreous humor sample using objective acceptance criteria. Implemented over three semesters with a >92% success rate, the experiment is adaptable to different course levels and resources. Headspace GC–MS offers additional advantages, including minimal sample preparation and reduced instrument maintenance.

The original article

Introducing Headspace Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry to Undergraduate Chemistry Students from a Forensic Toxicology Perspective

Devin C. Baer, and Michele M. Crosby*

J. Chem. Educ. 2026, 103, 1, 441–448

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.5c00118

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

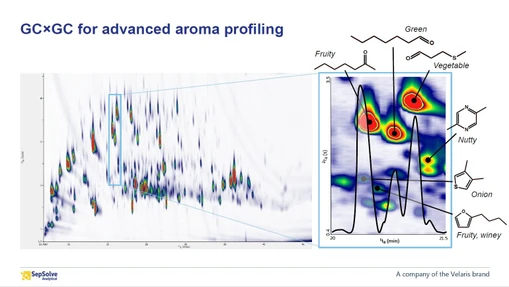

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is widely used across chemistry disciplines, from analysis of biodiesel feedstocks to pesticides residues in vegetables and even two-dimensional GC (GC × GC) such as GC × GC time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC × GC-TOFMS) in forensic science applications. (4−6) The two-dimensional GC of the GC × GC-TOFMS can provide more optimized separation of analytes compared to one-dimensional GC and the time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzer is an alternative to the quadrupole discussed earlier in this section. (6) In the environmental field, GC-MS can be used to detect pollutants related to microplastics and pesticide residues. (7,8) GC-MS and GC tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) is useful in food safety and quality assurance because of its ability to detect contaminants and assess ingredient quality. (9,10) GC-MS, including GC × GC-TOFMS and GC-MS/MS, is used in characterization of coal-derived liquids and petroleum exploration. (11,12) In forensics, these types of instrumentation are used to identify residues, like fire accelerants, explosive residues, or drugs at a crime scene, and to identify drugs, poisons, or other substances in biological samples. (1,6,13) In summary, a fundamental understanding of GC-MS will lend itself tremendously to any potential career field or discipline that may interest an undergraduate chemistry student.

In one application of headspace GC-MS, an aliquot of the biological sample is diluted with an internal standard solution and placed in a sealed glass vial. (1,14) The internal standard solution is a saline-based solution that optimizes the evaporation (sometimes called “salting out”) of the volatile compounds into the headspace portion of the vial, and it contains a compound that is similar in chemical structure to the analyte(s) of interest, The glass vial is heated to separate the volatile compounds from the biological matrix, and a sample of the headspace vapor containing the volatile compound is taken. (1,14) The concentration of the volatile analyte in the dilute aqueous sample is directly proportional to the concentration of the volatile analyte in the gas phase, or headspace, above the liquid. (14) Internal standard solution is added to a sample to give an indication of the extraction quality and aids in the concentration determination. The same concentration of the internal standard is added to the calibrators, controls, and case samples in a batch. (1) The ratio of the analyte response to the internal standard response is the most important factor to consider, not the absolute value of the analyte, in determining the concentration (or the qualitative presence/absence) of the analytes. By using this ratio, students can account for differences in analyte responses due to variables like extraction recovery, matrix effects, and injection volume. (1,2)

Relevance to Forensic Toxicology

Currently, very few published experiments exist for undergraduates involving forensic toxicology, (15) and even fewer involve volatile analysis. (16) Forensic toxicology laboratories routinely analyze samples for the presence of ethanol, methanol, acetone, and isopropanol. (1) Cases involving driving under the influence (DUI) and homicides are just a few examples targeted by these types of laboratories. (1,17−20) Ethanol, commonly referred to as alcohol, is the main type of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages and is considered the most commonly encountered substance in forensic toxicology casework. (1) In the U.S., most states have established a per-se limit for the blood alcohol concentration for drivers of 0.08 g/dL and violating this law could lead to prosecution for driving under the influence. Ethanol is also frequently encountered in post-mortem cases, such as homicides, traffic accidents, and alcohol poisonings. However, it is important to consider when interpreting ethanol concentrations that ethanol can be produced in the body after death by microorganisms breaking down the body. (1) Certain types of specimens collected after death, such as urine and vitreous humor (clear fluid inside the eye), are more resistant to this phenomenon and can be used to help determine antemortem ethanol consumption versus post-mortem production. (1) Isopropanol can be found in rubbing alcohol, so it is recommended that a different kind of antiseptic be used to clean the skin before a blood draw for a DUI. Isopropanol can also be found in various household cleaning products. It is also important in post-mortem forensic toxicology as it may be abused by chronic users or accidentally ingested. (1,19,20) Acetone is important as it is ta product of the metabolism of isopropanol, but it is also produced endogenously. High levels of acetone may be an indication of uncontrolled diabetes, so it is very important in post-mortem casework. (1,20) Methanol, sometimes known as wood alcohol, can be encountered in forensic toxicology casework, as it is found in improperly distilled alcoholic beverages and many household products. Methanol poisoning can be fatal due to the formation of the metabolite formaldehyde. Furthermore, methanol can be an artifact seen in embalmed specimens. (1)

While forensic toxicology laboratories use headspace gas chromatography–flame ionization (GC-FID) detection more commonly for the quantitation of volatile compounds, headspace GC-MS is a gold standard for identifying and confirming other types of volatile compounds such as 1,1-difluoroethane (DFE). DFE is commonly found in keyboard cleaners and has the potential for abuse, which is why forensic toxicology laboratories need the ability to detect it. DFE has been detected in driving under the influence cases as it has become anabused inhalant, due to the cheap cost and ease of access. (17,18)

The University of Tampa possesses a GC-MS equipped with a headspace autosampler; therefore, GC-MS was used rather than GC-FID for this experiment. Furthermore, GC-MS was strategically chosen to give students more practice with complicated data analysis provided by GC-MS in SIM mode. It is important to note that methanol was not chosen as a target for this experiment because of the difficulty in finding enough unique ions without interference from common environmental molecules.

Materials and Reagents

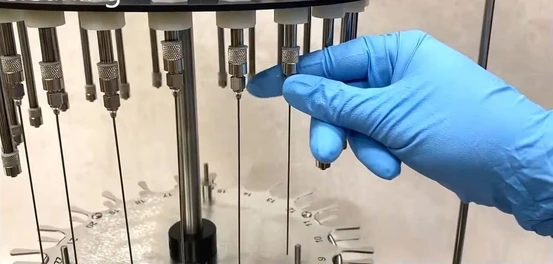

The following were purchased from Fisher (Hampton, NH): ethanol, acetone, and isopropanol. Endust for Electronics (Buffalo, NY) multi-purpose duster was used for the DFE standard. 20 mL headspace vials and caps were purchased from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA). A DB-624 column (20 m × 0.18 mm × 1.00 μm) was purchased from Agilent (Santa Clara, CA). The instrument used in this experiment was an Agilent 6890N gas chromatograph and 5973N mass spectrometer (operated in SIM mode) with a Gerstel MPS2 multipurpose autosampler (see Table 1 for additional instrument parameters). Helium was used as a carrier gas. A 2.5 mL Hamilton CTC and LEAP technologies GC PAL autosampler syringe: gastight was used.

Results and Discussion

There was a total of 43 students enrolled in the course over 3 semesters with an average grade on the assignment of 83 ± 11%. As part of this assignment, students quantitated ethanol concentrations and qualitatively identified acetone or isopropanol. One student did not complete the assignment as instructed and did not provide appropriate results for the analytes; therefore, the following data were compiled for 42 students unless otherwise stated. Of note, DFE is a recent addition to the experiment and was not used in previous semesters. It has been evaluated and determined to be a suitable qualitative compound for this experiment as an alternative or in addition to acetone and isopropanol. Additional information is provided below as part of the potential modifications to the experiment. It should also be highlighted that this course and thus this experiment are designed to prepare students for a career in forensic science based on feedback and advice from forensic science agencies. It mimics laboratory training and proficiency testing that forensic science analysts must undergo before being approved to conduct casework analyses. Therefore, the success of the experiment was determined by the student’s ability to report accurate results rather than student survey data or feedback.

The representative retention times are shown in Figure 1 for ethanol, acetone, isopropanol, and tert-butanol (internal standard). DFE was also included in the figure for easy reference. The peak that appears before DFE in Figure 1 represents a small volatile compound that appeared in all samples, including airblanks. If DFE is not used in the experiment, then it is recommended to include a solvent delay of 1 min. The average retention time of ethanol over 3 semesters (n = 42) was 1.60 ± 0.01 min. Acetone’s average retention time was 1.89 ± <0.01 min. Isopropanol’s average retention time was 2.00 ± 0.01 min. The average retention time of tert-butanol was 2.37 ± 0.02 min. See Table 2 gives a summary of the average retention times for each volatile compound. Of note, the variation of retention time primarily occurred between semesters due to routine annual maintenance. All 42 students’ data passed the calibration acceptance criteria with an average R2 value of the ethanol calibration curve of 0.995 ± 0.004 over 3 semesters (n = 42). Figure 2 shows the chromatograms produced by the SIM analysis of each volatile compound. This figure is an example of one of the components produced in the report generated by students during data processing, where students use these mass spectral data to evaluate and report data.

J. Chem. Educ. 2026, 103, 1, 441–448: Figure 1. Example total ion chromatogram of volatile compounds and retention times.

J. Chem. Educ. 2026, 103, 1, 441–448: Figure 1. Example total ion chromatogram of volatile compounds and retention times.

J. Chem. Educ. 2026, 103, 1, 441–448: Figure 2. Example SIM ions of each volatile compound.

J. Chem. Educ. 2026, 103, 1, 441–448: Figure 2. Example SIM ions of each volatile compound.

Conclusion

Students met learning outcomes and gained fundamental instrumental knowledge and hands-on experience through this experiment as they explored the concepts of chromatography and mass spectrometry. While students who completed this experiment had previous experience with GC-MS, this experiment introduced a new way of generating data reports. Students had to explain their conclusions based on these data reports as part of their postlab assignment, which provided firsthand practice of data analysis and communication skills. Trends in student results indicated that the experiment is very robust and reproducible, leading to a high success rate for students. This experiment offers a variety of modifications for instructors based on the number of students, student skill level, and resources available.