Are We Ready for It? A Review of Forensic Applications and Readiness for Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography in Routine Forensic Analysis

![<p>Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 1: One-dimensional GC total ion chromatogram showing co-elutions of volatiles from decomposition of remains [8].</p>](https://gcms.labrulez.com/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/Journal_of_Separation_Science_48_4_2025_Figure_1_One_dimensional_GC_total_ion_chromatogram_showing_co_elutions_of_volatiles_from_decomposition_of_remains_8_767d392a9b_l.webp)

Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 1: One-dimensional GC total ion chromatogram showing co-elutions of volatiles from decomposition of remains [8].

Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC) has been widely explored in forensic research to enhance separation and detectability across diverse evidence types, including drugs, fingerprints, toxicology, CBNR substances, and petroleum samples. By combining two independent separation mechanisms via modulation, GC×GC significantly increases peak capacity and is particularly valuable for nontargeted forensic analyses.

This review summarizes current forensic GC×GC research and evaluates both analytical and legal readiness for routine use. Applications are assessed using a technology readiness scale and examined against courtroom standards such as Frye, Daubert, Federal Rule of Evidence 702, and the Mohan criteria. Seven forensic application areas are categorized based on readiness levels, highlighting the need for increased validation, error rate analysis, and standardization to support future routine implementation.

The original article

Are We Ready for It? A Review of Forensic Applications and Readiness for Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography in Routine Forensic Analysis

Emma L. Macturk, Kevin Hayes, Gwen O'Sullivan, Katelynn A. Perrault Uptmor

Journal of Separation Science, Volume 48, Issue 4, 2025

https://doi.org/10.1002/jssc.70138

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC) is an analytical technique used to separate volatile and semi-volatile compounds in complex mixtures. GC×GC expands upon the traditional separation technique of one-dimensional gas chromatography (1D GC) by adjoining two columns of different stationary phases in series with a modulator [1]. Although 1D GC methods have limitations on resolution and detectability for trace compounds, GC×GC offers an increase in signal-to-noise ratio and overall larger peak capacity that enables more comprehensive separation of complex samples [2, 3]. The modulator, commonly referred to as the heart of GC×GC, preserves the separation from the first column by sending a short retention time window to be separated on the secondary column. Modulation allows for the analytes’ different affinities for each column to dictate their separation and increase overall peak capacity.

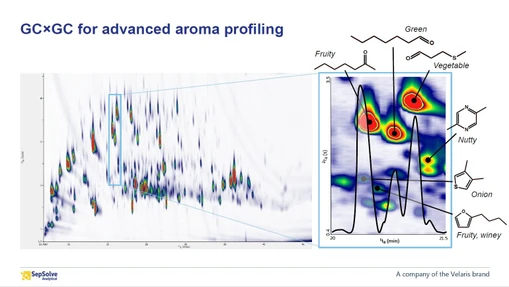

Multidimensional gas chromatography has developed and evolved since its conception in the 1980s. The need for better separation and sensitivity in complex samples has driven the evolution of GC×GC since it was first introduced [4-7]. Theory development pioneered in the 1980s was driven by the need for improved peak capacity [4, 5]. Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate the ability of GC × GC to resolve analytes that co-elute in 1D GC [8]. The first demonstrated success of GC×GC was published in 1991, resolving a 14-component, low-molecular-weight mixture [6]. The first formal definitions in the field were published in 2003 [9] and then updated in 2012 [7].

![Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 1 - One-dimensional GC total ion chromatogram showing co-elutions of volatiles from decomposition of remains [8].](https://gcms.labrulez.com/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/Journal_of_Separation_Science_48_4_2025_Figure_1_One_dimensional_GC_total_ion_chromatogram_showing_co_elutions_of_volatiles_from_decomposition_of_remains_8_767d392a9b_l.webp) Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 1 - One-dimensional GC total ion chromatogram showing co-elutions of volatiles from decomposition of remains [8].

Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 1 - One-dimensional GC total ion chromatogram showing co-elutions of volatiles from decomposition of remains [8].

![Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 2 - GC×GC-TOFMS total ion chromatogram demonstrating the resolving power of multidimensional separations [101].](https://gcms.labrulez.com/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/Journal_of_Separation_Science_48_4_2025_Figure_2_GC_GC_TOFMS_total_ion_chromatogram_demonstrating_the_resolving_power_of_multidimensional_separations_101_fc15fae89c_l.webp) Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 2 - GC×GC-TOFMS total ion chromatogram demonstrating the resolving power of multidimensional separations [101].

Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 2 - GC×GC-TOFMS total ion chromatogram demonstrating the resolving power of multidimensional separations [101].

In GC×GC, a sample is injected onto a primary column (1D column) of a desired stationary phase. The analytes within the sample elute from the 1D column according to their affinity for its stationary phase [1-3]. The modulator collects samples from the eluate for a set time period (e.g., typically 1–5 s) and then passes these collected plugs onto the secondary column (2D column) at a repeated interval, called the modulation period [1-3]. The 2D column separates the short injection from the modulator further, according to a different retention mechanism than the 1D column. Detectors for GC×GC have evolved from early detection methods using flame ionization detection (FID) and mass spectrometry (MS) to more advanced methods including high-resolution (HR) MS and time-of-flight (TOF) MS, as well as dual detection methods such as TOFMS/FID [10].

Current applications of GC×GC use its high peak capacity in fields, such as fuels and industrial chemicals, environmental analysis, foods and fragrances, and biological and forensic studies [1]. The technique of GC×GC was pioneered in 1991 and has developed greatly in the field of separation chemistry in terms of hardware, method development, and data processing over the past 30+ years [6]. Early applications from 1999 to around 2012 focused on proof-of-concept studies for forensic applications of GC×GC and then rapidly increased in number (Figure 3). In recent years, the areas of oil spill forensics and decomposition odor as forensic evidence have reached 30+ works for each application (Figure 3). This trend demonstrates a growing interest and wider acceptance of GC×GC in the forensic sphere.

3 Fingerprint Chemistry

Ridge characteristics from a deposited fingerprint are routinely used by forensic identification specialists to individualize a fingerprint to a suspect via the use of a fingerprint database. Partial fingerprints, or fingermarks, consisting of sweat and oil that are smudged or lacking a complete ridge pattern are not fit to undergo the identification process, although their chemical residue could still be useful to forensic chemists [61]. Though GC–MS has been used to characterize components of this residue, fingermark analysis using GC×GC–MS is in its infancy. Established GC–MS studies can determine donor class characteristics such as sex or relative age of a donor using biomarkers of octadecanol (C18) and eicosanol (C20) for sex determination and squalene and cholesterol for relative aging [62, 63]. Three manuscripts were identified to use GC×GC–MS for chemical analysis of fingerprint residue.

One proof-of-concept study for GC×GC–MS analysis of fingermarks was performed by Ripszam et al., in which the group used GC×GC-HRMS to identify 326 compounds in human sweat, one of the substituents of fingermark residue [20]. Of these compounds, 239 originated in the human body, and 41 were identified as anthropogenic, or originating as a contaminant outside the body [20]. Two studies directly analyzed fingerprint residue using GC×GC-TOFMS; one targeted method was performed for identifying seven analytes, and one study with focused on the extraction of residue from fired cartridges for exploiting chemical differences within suspects [19, 21]. Given the large peak capacity of GC×GC and the ability to perform nontargeted analysis of complex samples with large numbers of analytes, GC×GC performance in the former study was not exploited to its potential extent [19]. The second study investigated fingerprint residue from fired gun cartridges and demonstrated proof-of-concept work to differentiate residue from five volunteers in a forensic case setting [21]. These proof-of-concept studies could be extrapolated to fingermark profiling with applications for analyzing forensic evidence. Further analysis of fingermark residue in a nontargeted manner could improve the ability for trace compound detection within fingermark residue.

These preliminary studies are the first of their kind in this application to use GC×GC–MS to analyze their respective sample type within a forensic context. Additionally, these studies were published in 2023 and 2024; this recent interest in characterizing biological sebaceous excretions using GC×GC–MS expands research applications for GC×GC–MS in the forensic chemistry field. Several factors of the Daubert and Mohan criteria are not met by this application of forensic analysis. This application of two published studies does not lead to qualified expert witnesses available for testimony. Although one study addressed error rates of intra- and inter-sample variability, there are no known or acceptable limits for this application. Method development and additional supporting data are necessary to move this application beyond a TRL of 1.

6 Toxicology

To the contrary of the field of forensic drug chemistry that investigates drugs as physical evidence outside the body, the field of forensic toxicology focuses on the analysis of drugs from human specimens, either as the native drug molecule or as drug metabolites. Toxicology research often focuses both on samples from living individuals (often from blood, urine, or saliva samples) and on samples from deceased individuals through postmortem toxicology (often involving a wider range of sample specimens). Six works focusing on applications of forensic toxicology using GC×GC were identified in the literature, ranging from 2003 to 2018, which represented a broad range of proof-of-concept applications in various drug categories [16-18, 71-73].

LC, mostly in combination with various MS approaches, has largely been the main tool used for confirmatory analysis in forensic toxicology. However, there has been increasing interest in the nontargeted screening nature of GC×GC–TOFMS for its expanded ability to perform high-throughput screening of a wide array of analytes in a single method [16]. Another major benefit of this technique is the ability to physically resolve endogenous analytes within the matrix from exogenous compounds due to drug ingestion [18]. Early studies in forensic toxicological analysis using GC×GC–MS focused on the technique in application to anti-doping efforts as an analytical alternative to LC techniques. Several basic drugs, as well as opiates, opioids, cocaine, and benzodiazepines, were shown to be capable of analysis using GC×GC–MS methods so long as derivatization was applied to the sample in advance of injection [17, 18]. This derivatization step is important to make the analytes more amenable to gas chromatographic separation. Twelve psychoactive drugs, including MDMA, ketamine, and cocaine, were effectively analyzed without derivatization using GC×GC-FID recently and validated using Standard Practices for Method Validation in Forensic Toxicology guidelines set by the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS) [74, 75]. In the application of anti-doping, GC×GC-TOFMS has also been shown to reach the required sensitivity for the guidelines put in place by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) for at least 40 analytes of interest and for improved full-scan monitoring of certain drugs of interest, such as hydroxystanozolol, that are particularly challenging to detect without selected ion monitoring [18, 71]. The ability to detect toxicological evidence in a nontargeted manner is an advantage of using GC×GC for this purpose over LC.

Aside from doping agents, GC×GC has also been applied to other drugs of interest. Proof-of-concept studies have shown potential for eight different drugs in hair samples [16]. Validation studies have demonstrated the possibility of simultaneous detection of cannabinoids extracted from plasma and blood [72, 73]. The literature basis indicates a TRL of 1 due to the lack of repeated literature, inter-laboratory studies, lack of uncertainty and error reporting, and lack of supporting data through additional publications. Due to the large number of analytes being monitored in forensic toxicology, more supporting data are needed to move this field toward TRL 2. The validation studies on cannabinoids are a promising direction for drug monitoring as it begins to approach some concepts seen in TRL 3. Anti-doping research comparison to world standards set by WADA and quality validation by methods guidelines set by the AAFS also provides some promise toward the advancement of this application in terms of its TRL. Nevertheless, an increase in more recent work across the variety of drug analytes observed in forensic toxicology would be a valuable addition to the field. In terms of the Daubert criteria, although the technique has been peer-reviewed, published, and tested in some scenarios, it is not yet generally accepted, and error rates have not been characterized. Additional work should aim to assist in furthering the TRL scale through supporting data and error rate characterization to lend additional validity to the method for forensic toxicology analyses.

10 Summary and Outlook

Although GC×GC is not a new concept as of 2024, its application in the field of forensic chemistry has significantly expanded over the past two decades. The seven forensic chemistry applications discussed in this review are categorized in various stages of development for use in the forensic laboratory. Although not ready for routine analysis currently, all applications require research in the areas of intra- and inter-laboratory studies, development of figures of merit, and increased replication studies to move from a developmental phase of research to an established and “gold standard” method. However, it is of note that current research in all application areas is being conducted on commercially available instrumentation. This is a large step in the standardization of chromatographic methods when the instrument itself has already undergone a degree of standardization through commercial manufacturing. Research applications, such as fingerprints, CBNR, and toxicology, are in early stages of development with the establishment of basic theory and research but lacking development, supporting data, or any higher TRL level figure of merit or validation experiments (Figure 5). Drug chemistry analysis using GC×GC is slightly further developed at a TRL of 2, moving past proof-of-concept studies but requiring replication and validation for further progression (Figure 5). The application of ILR for arson investigation has shown development within the application, especially relating to data analysis, but lacks the replication of supporting data to fully move into a TRL of 3. Replication and repeatability studies allow oil spill forensics and decomposition odor applications to be categorized as higher TRLs (Figure 5). The few inter-laboratory studies conducted have shown promise in the ability to further develop validation through figures of merit. The development of chemometric techniques for analyzing and displaying data has been more heavily explored in recent years, which could also reduce some of the challenges associated with expert user necessity for GC×GC output interpretation.

Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 5 - TRL comparison of seven forensic chemistry applications using comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography in 2024. TRL, technology readiness level.

Journal of Separation Science, 48, 4, 2025: Figure 5 - TRL comparison of seven forensic chemistry applications using comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography in 2024. TRL, technology readiness level.

Although there are studies in every application area that compare GC×GC to GC using the same methods, few are direct comparison studies using methods from the Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science (OSAC) or ASTM. The optimization, validation, and replication of OSAC and ASTM methods are a critical component of technology readiness because standardization is a major development goal for new analytical technologies to be adopted into forensic laboratories. Within this process is the need for these methods to be translated from established ASTM methods or created into fully new methods. In addition to standardization and validation of sampling and chromatographic methods, the same standardization must occur within the data analysis sphere in order to use these techniques within a forensic laboratory. Although not specifically mentioned in any current works in the field of forensic GC×GC analysis, it is also likely that an increased emphasis on green chemistry may also come into play when looking forward to future standardized methods since sustainability is becoming a major focus for routine laboratories with high throughput.

General acceptance of a technology or forensic method is important in courtroom admittance, as seen as the basis for over 100 years of scientific evidence admittance. This principle is seen in the Frye and Daubert criteria, on which Federal Rule of 702 is based (Table 1). On the basis of the number of published and reviewed studies in the three higher TRL applications of ILR, oil spill, and decomposition odor, there is general acceptance in their respective scientific communities for the use of this new technology within the forensic sphere (Figure 3). The other four applications discussed in this review comparatively have less than half the number of publications as the two leading applications. Depending on their TRL, general acceptance could be established in subsequent years. TRL 1 applications have further to go for the research to be considered sufficient for general acceptance. Another courtroom concept touched on by authors of current literature addresses the need for an increase in the expertise of the forensic workforce for a new technique such as GC×GC to be adopted into routine forensic testing and laboratory spaces. The Mohan criteria in Canada and the US Federal Rule of 702 explicitly address the scientific expert's role, in this case the forensic analyst, in testimony. Both rules cover themes relating to the qualification and appropriate application of methods to the forensic evidence in question. The importance of a competent workforce of analytical chemists in forensics is reinforced by these requirements and should not be neglected when considering training and implementation from an academic standpoint as well as a forensic chemistry lens.

Researchers in the field of forensic chemistry have demonstrated the value of increased peak capacity and sensitivity from GC×GC and the positive outcome it has in increasing understanding of potential forensic evidence. Although some applications are still in their infancy in regard to exploration with GC×GC, more mature and developed research in oil spill forensics and decomposition odor indicates a push for readiness in routine forensic laboratories. Early readiness stage applications can learn from this TRL progression to inform workflows and determine the most valuable next research steps in terms of study design and validation. Although the research indicates that GC×GC might not be ready for implementation in forensic laboratories across all disciplines currently in 2024, there is great potential for its use and admission within the court system in the future.