Comparative Assessment of the Chemical Composition of Locally Cultivated and Imported Hops (Humulus lupulus L.) in Brazil Using Chemometrics

ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025: Graphical abstract

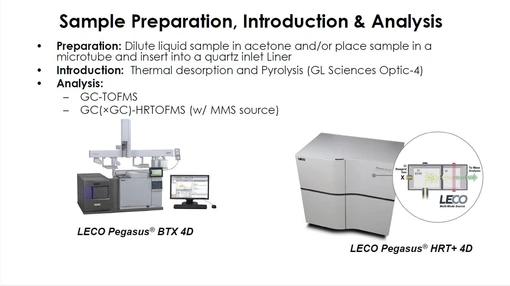

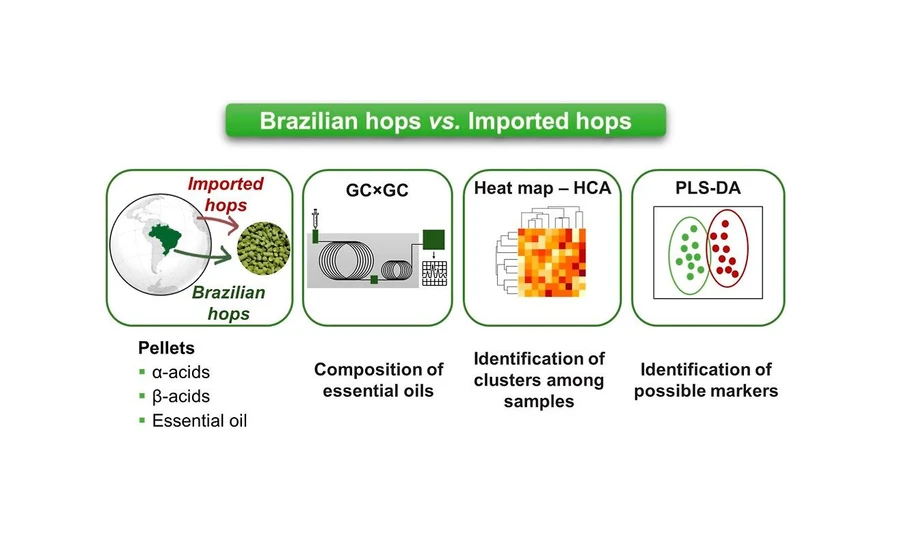

The expansion of hop cultivation in Brazil has increased interest in understanding its chemical characteristics. This study compared three Brazilian hop cultivars (Comet, Cascade, and Sorachi Ace) with imported hops using GC×GC–MS and chemometric tools, focusing on essential oils and α- and β-acids.

Results showed that Brazilian hops exhibited chemical profiles similar to imported hops of the same cultivar, clustering primarily by cultivar. While imported hops contained higher levels of myrcene and β-pinene, Brazilian hops showed elevated concentrations of several sesquiterpenes, highlighting their promising potential for the brewing industry.

The original article

Comparative Assessment of the Chemical Composition of Locally Cultivated and Imported Hops (Humulus lupulus L.) in Brazil Using Chemometrics

Letícia Fagundes Pereira, Stanislau Bogusz Júnior, Leandro Wang Hantao, Gabriela Aguiar Campolina, Amanda Francine Minetto, Andre Luis Carvalho Souza, Lucas Barboza de Mori, Maria das Graças Cardoso, Cleiton Antônio Nunes, and Marcio Pozzobon Pedroso*

ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsfoodscitech.5c00718

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Hops, responsible for imparting bitterness, flavor, and characteristic aroma to beer, have gained increased prominence in recent years, driven by changes in consumer preferences and the growing appreciation for beverages with differentiated sensory attributes. (1) In this context, hops have come to be used in much larger quantities than in traditional brewing methods, aiming to produce beers with more intense flavors and aromas. This increase in usage, along with the adoption of irrigation methods, genetic improvements, and the development of more efficient pesticides and fertilizers, has contributed to the global expansion of hop cultivation. (2−4)

Hops are originally cultivated in temperate regions, with the United States and Germany being the largest producers, accounting for approximately 77% of global production. As cultivation has expanded, hop-growing regions have spread to various parts of the world, including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Brazil. In Brazil, the growing number of breweries has driven higher hop consumption. As one of the world’s largest beer producers, the country relies heavily on imports, which reached about 57 million USD in 2020. This high demand, coupled with the need to lower production costs, has fostered the development of domestic hop cultivation. (5,6)

The first hop harvests in Brazil date back to 2017, and the crop has been expanding nationwide. In 2023, hop cultivation areas increased by 113% compared to 2022, totaling approximately 112 ha, with a focus on the southern and southeastern regions, because in some parts of the country, the shorter natural photoperiod requires the use of supplemental lighting. (7,8) This new scenario demands studies that evaluate everything from the genetic conditions of hop seedlings to the characteristics of hops used in brewing.

The quality and characteristics of hops can be influenced by several factors. Among the most relevant are the degree of ripeness at harvest, processing and pelletization methods, moisture control, and storage conditions. Additionally, chemical properties such as the content and composition of essential oils, as well as levels of α-acids and β-acids, are highly relevant to the aroma and bitterness attributes. (9) These characteristics are directly related to hop quality and the attributes they confer to beer, with an intrinsic relationship between chemical composition and sensory properties. Thus, the use of techniques to determine chemical characteristics is a valuable parameter for evaluating hop quality, highlighting the importance of understanding their chemical composition. (10−12)

Resins make up about 10 to 30% of hop dry matter and contain α- and β-acids that contribute to beer bitterness. (13,14) On the other hand, essential oil imparts the characteristic hop aroma and flavor to beer and is composed mainly of hydrocarbons (50 to 80%) and oxygenated compounds (up to 30%). (15−17)

Considering the importance of hop chemical composition, hop quality can be comparatively assessed. The quality of Cascade hops grown in Sardinia was evaluated in comparison with hops cultivated in the United States and New Zealand. The levels of α- and β-acids and essential oil composition were assessed, and compatible proportions of these acids and oil compounds were found across the different samples. (18) Hops from different cultivars cultivated organically and conventionally in Brazil were also compared in terms of essential oil composition and α- and β-acid levels. Minor chemical composition variations were observed among the different cultivars and within the same cultivar across the two cultivation methods. (19) The essential oil composition of Cascade hops cultivated in Brazil was compared with samples of the same cultivar grown in the United States. The essential oils of the Brazilian samples showed lower levels of myrcene, humulene, and caryophyllene, and higher levels of trans-β-farnesene, β-selinene, and α-selinene than those from the U.S. samples. (20) In another study, cones of Cascade and Chinook cultivars grown in Brazil were compared with commercial pellets of the same cultivars imported from the United States, considering the content and composition of essential oils. The results showed that 40% of the Brazilian samples presented essential oil content within the expected range, and regarding composition, the hops were mainly differentiated by cultivar type, with no distinction between Brazilian-grown hops and commercial pellets. (21)

Additionally, the adaptation of some hop cultivars to the northeastern region of Brazil has been evaluated. When comparing bitter acids, xanthohumol, and essential oils from hop flowers to commercial hop pellets, a similar profile was observed among samples from different growing locations, despite being in different hop forms. (22) Comparisons between hops grown in Brazil and imported cultivars have also been conducted using extracts obtained with dichloromethane (23) and through the volatile profile of the samples. (24) In both cases, differences were observed between Brazilian and imported samples, with compounds identified as being distinct among hops grown in different regions.

These findings demonstrate that hops of the same cultivar may exhibit different chemical characteristics depending on the cultivation region, resulting in site-specific properties and generating a regional identity. (25) However, considering the expansion of hop cultivation in Brazil, there are still few studies involving Brazilian hops and the evaluation of their chemical characteristics. Furthermore, there is a lack of studies assessing bitter acids and essential oils obtained through official methods, and comparing different hop cultivars cultivated and marketed in Brazil with the same imported cultivars, which are currently the most commonly used in beer production. Therefore, this study investigates the chemical characteristics of three hop cultivars (Cascade, Comet, and Sorachi Ace) produced and marketed in Brazil, comparing them with imported hops of the same cultivars.

2. Material and Methods

2.4. GC × GC–MS and GC × GC–FID Analyses

To perform chromatographic analyses, essential oil samples were diluted to obtain 5% (v/v) solutions in hexane and were analyzed in triplicate. A GC × GC system was a TRACE 1300 chromatograph equipped with an FID and a transmission quadrupole mass spectrometer (QMS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific-Waltham, MA, USA). Samples were introduced using the TriPlus RSH autosampler, into which 1 μL of sample was injected. The injector was operated at 250 °C with a split ratio of 1:10. The oven temperature program started at 60 °C, which was maintained for 3 min, and then the temperature was increased at 3 °C min–1 to 210 °C. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 0.5 mL min–1. The auxiliary gas was maintained at 20 mL min–1. Flow modulation was performed using an INSIGHT modulator (SepSolve Analytical–Waterloo, Canada). The modulation period was 5 s. The columns used in the first and second dimensions were Rxi-5 ms of 30 m × 0.25 mm (0.25 μm) and Rxi-17 ms of 5 m × 0.25 mm (0.25 μm) columns, respectively. Further analytical details are provided in our previous papers. (27,28) The FID temperature was 250 °C. For the mass spectrometer, the transfer line and ion source temperatures were 260 and 250 °C, respectively. Electron ionization (EI) was used to acquire the mass spectra in the m/z range of 50–350.

For data acquisition, Xcalibur software (Thermo Fisher Scientific–Waltham, MA, USA) was used, and the data were processed with GC Image software (GCI, TX, USA), allowing for the integration of the chromatographic peaks to obtain the peak areas. To identify the essential oil compounds, the mass spectra of each compound were compared with those contained in the NIST database, with a minimum similarity of 80% between the spectra required for compound identification. Furthermore, by injecting a homologous series of n-alkanes from C8 to C20, the linear retention indices (LTPRI) of the compounds were calculated using the van den Dool and Kratz equation. (29) The calculated LTPRI were then compared with those reported in the literature (NIST and Adams), with tolerated deviations of up to ±10 between the theoretical and experimental values. (30)

3. Results and Discussion

3.2. Essential Oils and GC × GC Analysis

In addition to α- and β-acids, essential oils are another parameter of great importance for hop quality, and their composition should be evaluated. Thus, the results of the essential oils of hops are displayed in Figure 3, as well as the reference values for each cultivar reported by imported brands. The data were also subjected to ANOVA and Tukey’s test and the results are presented in Table S2.

ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025: Figure 3. Essential oil content of hop samples.

ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025: Figure 3. Essential oil content of hop samples.

When comparing the obtained levels of essential oils with those expected according to the range reported by reference brands, (33) Brazilian hops Comet cmB1, Sorachi Ace sB2 and sB3 presented values below expectations, while imported hops presented levels compatible. The I1 brand packaging specified that the yields considered the average of the last harvests, and variations may occur. Lower essential oil contents in Brazilian hops could be due harvest variation, but this information was not available to the consumer. These variations may occur, for example, as a consequence of changes in climatic conditions, which have been reported to influence the composition of bitter acids and essential oils in hops cultivated within the same region across different years. (35) In addition, lower values can be also associated with factors related to the processing steps of Brazilian hops. After harvesting, several factors contribute to the reduction of the amount of essential oil in hops, such as the drying and pelletizing processes and storage conditions, especially when there is no control of temperature, since high temperatures contribute to the volatilization and loss of essential oil. (11,17) The lower oil content of Brazilian hops may also be associated with plant age, as plants with less than three years of cultivation may not have reached sufficient maturity to produce the expected levels of essential oil. (21) However, this information was not available for the samples analyzed as they were currently available in the market, and the fact that hop cultivation in the country is recent suggests that some of them may have been obtained from plants younger than three years, resulting in pellets with essential oil content below the expected values.

Finally, when comparing the essential oil content for each cultivar, it can be observed that the Brazilian Cascade hops presented levels equivalent to their imported counterparts and to values reported in the literature. (18,20,36) When applying ANOVA and the Tukey test (Table S2), it is noted that the two Brazilian samples are equivalent to the imported sample cI2, while the imported sample cI1, which presented a lower essential oil content, differs significantly from the samples cI2 and cB1. For the Comet cultivar, only the B2 brand was comparable to the imported samples, resenting essential oil content equivalent to that of the imported sample cmI2. For Sorachi Ace, none of the Brazilian samples matched the essential oil content of the imported ones and all samples presented essential oil contents that differed significantly from each other. Given that Brazilian hops had α-acid levels compatible with the imported cultivars but some exhibited lower essential oil content, it was essential to evaluate the composition of these oils to determine if the chemical profile of Brazilian hops was comparable to that of imported hops. Additionally, it was important to investigate whether there was a trend toward the production of specific compounds that might differentiate Brazilian hops from imported ones.

3.3. Chemometrics

To gain a deeper understanding of these differences, an exploratory data analysis was conducted using unsupervised HCA and heat map construction. This analysis aimed to identify clusters among the samples. The HCA shown in Figure 4 reveals clustering based on hop cultivar, without distinctions related to sample origin. Additionally, it was possible to identify the most prominent variables for each cultivar, with a consistent pattern observed in samples of the same cultivar, regardless of their origin. Another notable finding is the clustering of both imported and Brazilian samples, observed in the I2 and B2 brand samples of the Comet cultivar, as well as in the I1 and B1 brand samples of the Cascade cultivar. For the Sorachi Ace cultivar, it is observed that the sB2 sample is grouped with the imported samples sI1 and sI2, indicating a greater similarity between their characteristics than the sB3 sample. Similarly, for the Comet cultivar, the B2 brand sample also grouped with the imported ones, which may be evidence of the greater proximity of the samples of this brand with the imported hops. It is also possible to observe the clustering between the Sorachi Ace and Cascade samples, suggesting similarities between these two cultivars. Both have an aroma profile in which the sweet fruity and citrus characteristics stand out, which should contribute to this clustering. (32)

ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025: Figure 4. Heat map of the triplicate of hop essential oil of cascade (c), comet (cm) and sorachi ace (s) samples, and HCA of samples and compounds.

ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025: Figure 4. Heat map of the triplicate of hop essential oil of cascade (c), comet (cm) and sorachi ace (s) samples, and HCA of samples and compounds.

In view of the results presented, there are similarities between hops grown in Brazil and their imported counterparts, which demonstrate great potential for Brazilian production. Nevertheless, there is a need for greater attention to the postharvest processing steps to ensure the integrity of essential oils and mitigate losses. Regarding the aromatic characteristics of hops, PLS-DA analysis revealed some differences for those grown in Brazil, with a higher concentration of some essential oil compounds, such as selinene isomers, than in imported hops, which may indicate specific characteristics of hops grown in Brazil. However, this conclusion cannot be definitively drawn due to the limited number of hop samples, batches and cultivars evaluated. Therefore, future analyses require a larger number of samples, including those from different batches and harvests, to confirm the evidence observed in this study. Furthermore, future work would also benefit from a more comprehensive evaluation of the chemical and sensory characteristics of hops, along with a sensory analysis of beers produced with these hops, to determine whether these compounds contribute unique attributes to Brazilian hops. Nevertheless, this study represents an important initial assessment of the quality of Brazilian hops and provides a basis for more comprehensive future investigations.