Molecular Sensory Analysis Confirms Wood Smoke Exposure as a Source of Smoky Off-Flavors in Fermented Cocoa

J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 31, 19663–19669: Graphical abstract

Smoky off-flavors are among the most common taints in fermented cocoa. Although previously attributed to overfermentation, this study confirms that wood smoke exposure during drying is a key source. Using gas chromatography–olfactometry and aroma extract dilution analysis, 2-methoxyphenol, 3- and 4-methylphenol, 3- and 4-ethylphenol, and 3-propylphenol were identified as major smoky odorants, with 2,6-dimethoxyphenol also contributing.

Quantitative analysis of naturally smoked cocoa revealed 2-methoxyphenol, 4-methylphenol, and 3-ethylphenol as the most potent compounds. Their presence in both husks and nibs indicates significant diffusion, suggesting that husk removal alone cannot effectively reduce smoky taints in cocoa.

The original article

Molecular Sensory Analysis Confirms Wood Smoke Exposure as a Source of Smoky Off-Flavors in Fermented Cocoa

Franziska Krause, and Martin Steinhaus*

J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 31, 19663–19669

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5c06046

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Chocolate products are popular snacks and desserts, eaten worldwide, regardless of age or social class. The basis for chocolate products is the seeds of the tropical cocoa tree, Theobroma cacao L., known as cocoa beans. The tree’s origins can be traced back to Latin America; however, it has since become distributed worldwide. Today, the main agricultural production region for cocoa is West Africa, but Southeast Asia and Latin America producers also contribute to the world market. (1−3)

The flowers of the cocoa tree grow directly on the trunk and big branches. They develop into mature fruits known as pods. The pods vary considerably in size, color, and shape, and contain the cocoa beans covered by a viscous, sugary, and adhesive cocoa pulp. (4,5) After harvest, beans and adherent pulp are fermented in heaps or wooden boxes. The fermentation lasts 2 to 10 days, depending on the fermentation method and the cocoa variety. During fermentation, a wide range of microorganisms, including yeasts, lactic acid bacteria, and acetic acid bacteria, convert the sugars of the pulp into ethanol and organic acids, causing the temperature to rise. Diffusion of acetic acid into the beans causes the death of the embryo. Polyphenols and proteins undergo oxidative polymerization, resulting in the typical brown color, reduced bitterness, and reduced astringency. (6−8) After fermentation, the cocoa beans are spread out and regularly turned to initiate the drying process. At the end of the drying period, the moisture content of the beans should be <8% to avoid microbial growth during storage and shipment. Depending on climatic conditions, sun-drying might not be sufficient, thus making additional artificial drying necessary. (6,9) Fermented and dried cocoa beans are shipped worldwide.

In the target country, most cocoa beans are processed into chocolate. A typical chocolate manufacturing process starts with the beans being crushed and deshelled to obtain cocoa nibs. During the following roasting step, aroma precursors formed in fermentation react to characteristic chocolate odorants. Roasted cocoa nibs are ground and milled to produce cocoa liquor. Some cocoa liquor is further processed into cocoa butter and cocoa powder. For chocolate production, cocoa liquor is mixed with sugar and further milled. Potential additional ingredients include cocoa butter, emulsifiers, flavorings, and milk powder.

Chocolate is particularly valued for its characteristic aroma and smooth mouthfeel. The molecular background of cocoa and chocolate aroma has been intensively studied, leading to the identification of ∼20–30 key odorants. (10−14) Some other compounds, however, have the potential to impart atypical or even unpleasant odor notes. Occasionally, batches of fermented cocoa are tainted with smoky, moldy, fecal, cheesy, mushroom-like, or coconut-like off-flavors. The odorants responsible for these flavor deviations have recently been identified. (15−17) For example, the smoky off-flavor was attributed to phenols such as 2-methoxyphenol, 3- and 4-methylphenol, 3- and 4-ethylphenol, and 3-propylphenol. (17) However, no attempt was made in this study to clarify the origin of the off-flavor compounds. Nevertheless, wood smoke contact during artificial drying has been discussed as a possible source, as well as overfermentation. (1,2,18−24) So far, no study has shown a clear relationship between the observed smoky off-flavors and the proposed underlying causes.

To fill this gap, our study first aimed to screen a sample of fermented cocoa beans that had been intentionally exposed to extreme levels of wood smoke in an experimental setting for odor-active compounds by gas chromatography–olfactometry (GC–O) (25) and aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA). (26) This worst-case scenario should ensure that no compounds contributing to the smoky off-flavor were overlooked. Targeted quantitation of the resulting potential off-flavor compounds was then extended to two cocoa samples with authentic wood smoke contact during drying in the origin. The low number of these samples was due to the problem that producers of high-quality cocoa would not allow experiments with wood smoke contact on-site in their processing facilities, while producers who used wood fires in the drying process with insufficient dissipation of the smoke tend not to admit their inappropriate processes. Quantitation was separately applied to nibs and husks, as a recent study has shown that cocoa odorants may be unevenly distributed between both. (16)

Materials and Methods

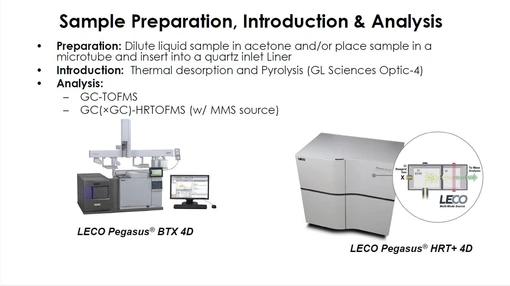

GC–O/FID

The system used for GC–O analysis consisted of a trace gas chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Dreieich, Germany) equipped with a cold on-column injector, a flame ionization detector (FID), a custom-made aluminum sniffing port, (30) and a DB-FFAP column, 30 m × 0.32 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness (Agilent; Waldbronn, Germany). The carrier gas was helium at a constant flow of 1.0 mL/min. The injection volume was 1 μL. The initial oven temperature of 40 °C was held for 2 min and then increased to 230 °C by 6 °C/min. The final temperature was held for 5 min. A Y-shaped glass splitter connected to the end of the column delivered the effluent through two uncoated but deactivated fused silica capillaries (50 cm × 0.25 mm i.d.) simultaneously to the FID (250 °C base temperature) and the sniffing port (230 °C base temperature). GC–O analyses were performed by trained assessors with >3 months of experience in GC–O of odorant mixtures. Training included weekly sensory testing on odorant recognition, flavor language, and anosmia. (25) During a GC–O analysis, the FID chromatogram was plotted by a recorder. The assessor placed the nose directly above the sniffing port and marked the position of each odor-active region together with the odor description in the FID chromatogram. The odorants’ retention indices (RIs) were calculated by linear interpolation from the retention times of the odor-active regions and the retention times of adjacent n-alkanes.

Heart-Cut GC–GC–HRMS

The two-dimensional heart-cut GC–GC–high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) system used for structure elucidation and quantitation consisted of two Trace 1310 gas chromatographs (Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected with a Deans switch (Trajan; Ringwood, Australia), and a high-resolution Q Exactive GC Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The first GC was equipped with a TriPlus RSH autosampler, a programmed temperature vaporizing (PTV) injector, and a DB-FFAP column, 30 m × 0.32 mm i.d., 0.25 μm thickness (Agilent); an FID (250 °C base temperature) and a custom-made sniffing port served as monitor detectors. The carrier gas was helium at a constant flow of 1.0 mL/min. The injection volume was 1–2 μL. The initial oven temperature of 40 °C was held for 2 min and then increased to 230 °C by 6 °C/min. The final temperature was held for 5 min. The end of the column was connected to the Deans switch, which directed the column effluent time-programmed through uncoated but deactivated fused silica capillaries (0.25 mm i.d.) either to the monitor detectors or via a heated hose (250 °C) to a liquid nitrogen-cooled trap. The trap was connected to the column in the second GC, which was a DB-1701 or DB-FFAP column, 30 m × 0.25 mm, i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness (Agilent). The initial temperature of the second oven was 40 °C, held for 2 min, and then increased to 230 °C by 6 °C/min. The final temperature was held for 5 min. The end of the second GC column was connected to the mass spectrometer operated in high-resolution mode. Electron ionization (EI) and chemical ionization (CI) modes were applied for structure assignment using scan ranges of m/z 35–260 and m/z 85–260, respectively. The reagent gas used in CI mode was isobutane. Quantitations were performed in the CI mode with a scan range of m/z 90–280. Data evaluation was accomplished with the Xcalibur software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Results and Discussion

Concentrations and OAVs of Smoky Odorants

To substantiate the differences between the reference sample and the experimentally smoked sample, all compounds potentially contributing to the smoky off-flavor were quantitated using GC–MS in combination with deuterated odorants as internal standards (cf. Supporting Information file, Table S2). The quantitations included 2-methoxyphenol, 3- and 4-ethylphenol, 2,6-dimethoxyphenol, and 3- and 4-methylphenol, i.e., the six odorants that resulted from the previous screening experiments, and in addition 3- and 4-propylphenol, which had recently been reported in cocoa with smoky off-flavors. (17) The quantitations were extended to two cocoa samples that had been authentically exposed to wood smoke during the drying process in the origin and exhibited a pronounced smoky off-flavor. Moreover, quantitation was separately applied to nibs and husks for three reasons: (1) An uneven distribution between nibs and husks of the cocoa bean has been demonstrated for different substances including cadmium (35) and the off-flavor compounds (−)-geosmin and 3-methyl-1H-indole. (16) (2) Given the superficial contact of the cocoa beans with the wood smoke during drying, higher concentrations of smoky off-flavor compounds in the husks than in the nibs could be expected. (3) Subsequent cocoa processing includes a winnowing step to remove husks, while the nibs fraction is further processed. However, a technically unavoidable proportion of husks remains in the nibs fraction. It might still be sufficient to substantially contribute to the total amount of the smoky off-flavor compounds.

The results of the quantitations are detailed in Table 2; individual concentration data used for mean calculations and standard deviations are available in the Supporting Information file, Tables S3–S10. The experimentally smoked cocoa showed substantially higher concentrations than the reference cocoa in the nibs and the husks. The increase in concentration during smoking strongly depended on the individual substance and varied between ∼3-fold and ∼50-fold in the nibs and between ∼9-fold and ∼400-fold in the husks. In agreement with the superficial wood smoke contact, the odorant concentrations in the husks of the smoked sample were higher than those in the nibs─by a factor of 6 to 25.

J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 31, 19663–19669: Table 2. Concentrations (μg/kg) of the Odorants with Smoky Odor Quality in Cocoa Nibs and Husks: Reference without Off-Flavor vs. the Experimentally Smoked Cocoa and Two Samples with Authentic Wood Smoke Contact during the Drying Process in the Origin

J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 31, 19663–19669: Table 2. Concentrations (μg/kg) of the Odorants with Smoky Odor Quality in Cocoa Nibs and Husks: Reference without Off-Flavor vs. the Experimentally Smoked Cocoa and Two Samples with Authentic Wood Smoke Contact during the Drying Process in the Origin

Another factor that influences the impact of an off-flavor compound is its exact odor quality. At the same OAV level, a compound with a very unpleasant odor note may be more offensive than a compound with a less unpleasant character. This may also influence the perception of the smoky cocoa odorants in the current study. Although a smoky odor note characterizes all compounds in Tables 1–3, they differ in their nuances. For example, 2-methoxyphenol with its somewhat sweet kind of smokiness may be less offensive and thus contribute less to the off-flavor than, e.g., 4-methylphenol with its unpleasant horse dung-like note (cf. Table 1). This may put into perspective that in all nibs and husks samples, 2-methoxyphenol showed the highest OAVs among all compounds investigated. However, in the off-flavor samples, additionally, 4-methylphenol, 3-ethylphenol, and 2,6-dimethoxyphenol showed OAVs >1, and the 2-methoxyphenol concentration was consistently beyond the previously suggested maximum tolerable concentration. (17) In agreement with the previous study, (17) 4-methylphenol and 3-ethylphenol always showed the second and third highest OAVs after 2-methoxyphenol, suggesting their substantial role in the overall off-flavor. By contrast, the propylphenols are likely of minor importance for the off-flavor. The concentration of 3- and 4-propylphenol was determined as a sum, and the corresponding OAVs provided in Table 3 were─in the sense of a worst-case concept (i.e., assuming 100% 3-propylphenol)─in the first instance calculated with the lower OTC of 3-propylphenol (2.0 vs 3700 μg/kg). Considering, however, that a substantial percentage of the sum is attributable to the virtually odorless 4-propylisomer, (17) it becomes clear that even the sum of the isomers (25.5 μg/kg max) is far below its OTC of 3700 μg/kg. Conservatively interpreted, 3-propylphenol, if at all, could contribute only marginally to the off-flavor.

To better visualize the effect of husk removal on the amount of the off-flavor compounds, their absolute distribution between nibs and husks was calculated from the relative amounts of nibs and husks in the cocoa beans (80:20; m/m) and the respective concentrations (Supporting Information, Table S11). The results for the major off-flavor compounds 2-methoxyphenol, 4-methylphenol, 3-methylphenol, 4-ethylphenol, and 3-ethylphenol are depicted in Figure 1. Unlike the experimentally smoked sample, in both samples with authentic wood smoke contact, the major part of the off-flavor compounds was localized in the nibs. Thus, even if performed very effectively, winnowing cannot substantially reduce the smoky off-flavor compounds.

J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 31, 19663–19669: Figure 1. Odorant distribution (m/m) between the nibs and the husks of the cocoa beans: reference cocoa without off-flavor vs experimentally smoked cocoa and cocoa with authentic wood smoke contact 1 and 2. Data were calculated from the mean concentrations (n = 3) in nibs and husks (cf. Table 2) and a gravimetric nibs/husks ratio of 80/20 (cf. Supporting Information file, Table S11).

J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 31, 19663–19669: Figure 1. Odorant distribution (m/m) between the nibs and the husks of the cocoa beans: reference cocoa without off-flavor vs experimentally smoked cocoa and cocoa with authentic wood smoke contact 1 and 2. Data were calculated from the mean concentrations (n = 3) in nibs and husks (cf. Table 2) and a gravimetric nibs/husks ratio of 80/20 (cf. Supporting Information file, Table S11).

In conclusion, this study confirmed wood smoke exposure as one source of smoky off-flavors in fermented cocoa and clarified the underlying compounds. A comparative AEDA applied to a fermented cocoa sample that had been intentionally exposed to extreme levels of wood smoke in an experimental setting confirmed previously identified off-flavor compounds 2-methoxyphenol, 4-methylphenol, 3-ethylphenol, 3-methylphenol, 4-ethylphenol, and 3-propylphenol (17) and revealed 2,6-dimethoxyphenol as an additional smoky smelling compound. Quantitative analyses, which additionally included two cocoa samples with a confirmed history of correct fermentation and authentic wood smoke contact during drying in the origin, followed by OAV calculations, suggested that particularly 2-methoxyphenol, 4-methylphenol, and 3-ethylphenol contributed to the smoky off-flavor. 2,6-Dimethoxyphenol showed the overall highest difference between the smoky samples and the reference without off-flavor (>100 times between the reference nibs and the nibs of authentic smoke contact sample 2) and has not yet been reported from overfermented cocoa. (1,21) 2,6-Dimethoxyphenol may thus be suitable as a marker compound for wood smoke contact, as previously suggested by Lehrian et al., (23) but due to its relatively high OTC is unlikely to have a substantial impact on the off-flavor. In the samples with authentic wood smoke contact, the major part of the off-flavor compounds had already diffused into the nibs. Consequently, husk removal by winnowing cannot substantially reduce the smoky off-flavor compounds.