Nontargeted Screening of Fingermark Residue Using Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography–Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry for Future Use in Forensic Applications

J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 10, 2299–2309: Graphical abstract

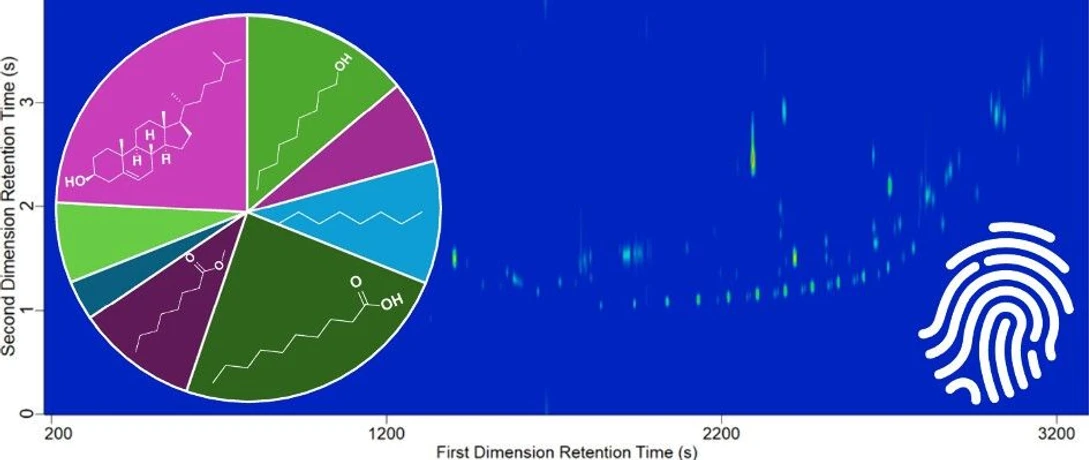

Fingerprints are a cornerstone of forensic evidence, but their chemical complexity often limits analysis using conventional GC-MS. In this proof-of-concept study, a nontargeted workflow based on comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC×GC-TOFMS) was developed and optimized for fingermark residue analysis.

Two extraction approaches were evaluated, and solvent extraction using cotton swabs provided the best reproducibility and analyte recovery. The optimized workflow identified 70 compounds, distinguishing exogenous cosmetic residues from endogenous fingermark components. The enhanced chromatographic separation achieved by GC×GC-TOFMS allowed improved donor differentiation and demonstrates the potential of nontargeted fingermark screening in forensic trace analysis.

The original article

Nontargeted Screening of Fingermark Residue Using Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography–Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry for Future Use in Forensic Applications

Emma L. Macturk, and Katelynn A. Perrault Uptmor*

J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 10, 2299–2309

https://doi.org/10.1021/jasms.5c00258

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Deposited fingerprints are routinely used in forensic investigations to identify a suspect. Ridge characteristics and patterns of a deposited fingerprint are used to individualize the print to a suspected donor. (1) Partial fingerprints that lack a complete ridge pattern often cannot be used for this individualization process. (2) The fingerprint residue, or fingermark, contains traces of sweat and oil secreted by the donor’s sebaceous glands. (1,3) The analyses of these organic components from the sebaceous glands have historically been conducted using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and inform how fingermark composition could advance suspect investigations in legal proceedings. (2−4)

Fingermark donor characteristics such as relative age and sex have been studied using various analytical techniques including GC-MS. Successful sex determination has been carried out using ultra high performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS), and GC-MS to establish amino acid and lipid biomarkers. (2,5,6) Relative donor age determination (i.e., whether a donor is a postpubescent adult or prepubescent child) has been studied with GC-MS using lipid ratios like cholesterol and squalene in fingermarks. (3,4) This has been confirmed by two additional studies using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis which found more branched long chain fatty acids esterified with alcohols to be present in adults compared to children. (7,8) Donor class identification studies of sex and relative age demonstrate forensic value in exploring the chemical profile of fingerprints. In addition to the compounds noted above that have been commonly identified in fingermark residue, fingermarks also have been identified as containing long chain fatty acids and fatty alcohols, wax esters, benzoic acid esters, and small vitamins. (9−13)

Contamination from exogenous compounds in fingermark residues based on the idea of touch chemistry could be used to associate an individual with a deposited fingermark. If an individual donor comes into contact with forensically relevant exogenous components, those compounds could be deposited in a fingermark left at a crime scene. (14,15) Personal care products such as sunscreen and cosmetic products have been resolved from fingermark residue in the literature and their usage was found to be variable at the individual level. (5,16) Sunscreen and insect repellent brands have been differentiated with MALDI-MS which would make lifestyle conclusions more specific to an individual who might buy one brand over another. (14) Lifestyle choices including beauty products and dietary information have been shown to differentiate donors based on fingermark and other residue sampled from cellular phones. (17)

GC×GC-TOFMS has been used to classify exogenous and endogenous compounds in human sweat, a matrix related to fingermark residue. (18) GC×GC-TOFMS has also been used to differentiate individuals who have touched fired cartridges. (19) Only one study has investigated clean latent fingermark residue using GC×GC-TOFMS. (20) That study targeted seven fingermark analytes to compare analyses by 1D GC-MS and GC×GC-TOFMS. Although GC×GC-TOFMS was found to differentiate between fingermark sources better than 1D GC-MS, fingermark chromatograms of a clean, washed hand deposited prints with no coelutions by GC-MS analysis, and therefore no immediate benefit to GC×GC-TOFMS was found when looking solely at derivatized targeted components. (20) However, the authors stated that GC×GC-TOFMS could be beneficial in forensic investigations for source attribution of exogenous compounds excreted from a suspect, (20) though this has never been attempted experimentally in the literature. Additionally, a study which used GC-MS for fatty acid analysis from fingermarks also referred to the benefits of using GC×GC-TOFMS for this type of forensic application. (13) A nontargeted method for resolving potential exogenous compounds, either excreted from the body or present through touch chemistry, could be a useful additional tool for forensic investigations of fingermark residue and seems to be desired by those conducting 1D GC-MS analyses in the literature.

In this study, a method for sample extraction and nontargeted analysis of the fingermark residue was developed and optimized using GC×GC-TOFMS. This method was then applied as a proof-of-concept study to the nontargeted screening of the fingermark residue for exogenous compounds (cosmetic products). The separation capacity and increased analyte detectability offered by GC×GC-TOFMS have the potential to provide substantial benefit in the nontargeted analysis of fingermark residue where endogenous fingermark components from sweat and oil can be resolved chromatographically from other exogenous components in the residue.

Experimental Methods

GC×GC-TOFMS Conditions

For initial GC-TOFMS and GC×GC-TOFMS (Pegasus BT 4D GC×GC-TOFMS) analyses, oven temperatures and conditions are listed in Table 1. GC-TOFMS samples were run with a mass spectral acquisition rate of 20 spectra/s and two-dimensional samples were run with a 200 spectra/s acquisition rate to reflect the difference in peak width from the two techniques. The mass range was set to 35–500 m/z with an extraction frequency of 32 kHz for both the 1D and 2D detections. The electron ionization energy used was 70.0 eV.

Data Processing

Samples were processed in ChromaTOF software version 5.56 with a data processor version 1.2.0.6 (LECO Corporation, Saint Joseph, MI). Peaks in 1D GC samples were identified with a minimum signal/noise ratio of 10. In all GC×GC samples, peaks were identified using a minimum signal-to-noise ratio of 700 and a minimum stick count of 3. Mass spectra were searched in the NIST Mass Spectral Library version 3.0, 2023, with a minimum spectral similarity of 700 for a match and relative abundance threshold of 10. ChromaTOF Tile (LECO Corporation) was used to determine analytes with the highest Fisher ratio (F-ratio) between donors in cosmetic application. Tile-based software allows for the class comparison of chromatograms to one another to extract relevant features that differentiate samples. Raw. SMP files were imported into ChromaTOF Tile and sorted based on F-ratio, a measure of class-to-class variation divided by within-class variation. High F-ratios represent analytes that are different between classes but consistent within a class. Samples were labeled according to the donor, resulting in five classes representing five donors with three replicates per class. A tile grid was overlaid in 2D chromatographic space to compare raw MS signals, which are considered “hits” if they meet the set thresholds. A tile size of 4 (1D) and 31 (2D) were autocalculated in the software based on average peak widths (1D) and heights (2D). A signal-to-noise threshold of 500 and F-ratio threshold of 20 were used to filter out low priority hits. Analyte identification was conducted using the mainlib library (NIST) and confirmed with ChromaTOF library matches. The hits were ranked in the hit list according to the highest F-ratio values. Hits were rejected and removed from further analysis based on the following criteria: (1) the hit was column bleed, (2) the same hit crossed multiple tile spaces, and (3) there were two or more hits within one tile so redundant hits were removed and only one hit would be accepted. The first 20 accepted hits were used in a principal component analysis (PCA) of the five donors using a built-in PCA function in the ChromaTOF Tile software.

Results and Discussion

Initial 1D and 2D Analyses

Initial samples were analyzed in 1D GC mode and then in GC×GC mode. Compound classes identified in 1D mode included fatty alcohols, fatty acids, wax esters, sterols, and precursors. In 1D mode, 15 compounds were identified using the NIST library (Figure 2A). Although some other peaks existed in the chromatogram, they either did not exceed the signal-to-noise (S/N) threshold of 10 or did not have a high enough library search value for confident identification.

J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 10, 2299–2309: Figure 2. (A) Total ion current (TIC) of a one-dimensional chromatogram of a fingermark residue (normalized). Fingermark analytes of interest: (1) nonanal, (2) tetradecanoic acid, (3) isopropyl myristate, (4) pentadecanoic acid, (5) hexadecanoic acid, () isopropyl palmitate, (7) 1-octadecanol, (8) stearic acid, (9) 13-docosenamide, (10) squalene, (11) cholesterol, (12) palmitelaidic acid, (13) 9-tetradecenoic acid, hexadecyl ester, (14) 9-hexadecenoic acid, hexadecyl ester, (15) 9-hexadecenoic acid, octadecyl ester. (B) TIC contour plot of fingermark residue, same volunteer as (A), analyzed in GC×GC mode.

J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 10, 2299–2309: Figure 2. (A) Total ion current (TIC) of a one-dimensional chromatogram of a fingermark residue (normalized). Fingermark analytes of interest: (1) nonanal, (2) tetradecanoic acid, (3) isopropyl myristate, (4) pentadecanoic acid, (5) hexadecanoic acid, () isopropyl palmitate, (7) 1-octadecanol, (8) stearic acid, (9) 13-docosenamide, (10) squalene, (11) cholesterol, (12) palmitelaidic acid, (13) 9-tetradecenoic acid, hexadecyl ester, (14) 9-hexadecenoic acid, hexadecyl ester, (15) 9-hexadecenoic acid, octadecyl ester. (B) TIC contour plot of fingermark residue, same volunteer as (A), analyzed in GC×GC mode.

Exogenous Compound Screening

The optimized method for analyzing fingerprints was applied to a set of fingermarks from five donors to screen for exogenous component contamination and variability between donors. Replicate samples from each of the donors displayed a relatively low intrasample variability for the common fingerprint residue analytes of squalene and cholesterol. Donor 4 displayed the lowest intrasample variability of the five subjects with % RSD values for cholesterol and squalene of 9.10% and 8.40% respectively. The highest intrasample variability was displayed in donor 2 with 38.18% and 22.70% for cholesterol and squalene. Cholesterol was detected in one of three replicate residues from donor 3, and squalene was detected in two of three replicate samples from that donor; therefore, sample size was not large enough to calculate % RSD. Sweating characteristics, the donor themselves, deposition force, and the portion of the finger touching the substrate where residue was deposited are known to be factors that categorize a fingermark donor into strong, medium, or weak donation abilities. (25,27,28) In this study, volunteer 3 could be designated as a “weak” fingerprint donor, having a decreased ability to deposit residue onto a surface or an uneven deposition force when depositing fingermarks. Intradonor variability measured by % RSD values was consistently lower (i.e., less variable) than interdonor variability in the literature (10,12) and also within this study. A larger study targeting a wider range of analytes would support this finding.

Residues from three donors contained exogenous compounds with a relatively high variability. Five exogenous analytes were resolved from fingerprint residue: diisopropyl adipate (cosmetic), octisalate (sunscreen), octocrylene (sunscreen), avobenzone (sunscreen), and α-tocopheryl acetate (vitamin E acetate) (Figure 6C). α-Tocopheryl acetate can be found in moisturizing cosmetic products such as vitamin E acetate. The presence of vitamin E acetate could indicate that these three donors had contact with moisturizing cosmetic products on the day of sampling. Avobenzone, octocrylene, and octisalate were found in five residues originating from one donor. These three analytes are UVB blockers commonly found in sunscreen ingredients. (17) The presence of three UVB blockers in one donor and the absence of those analytes in all other donors in this study could be used to infer lifestyle choices of sunscreen wear (Figure 6A). A previous study found that UVB blockers avobenzone, octocrylene, oxybenzone, and octinoxate were markers for differentiation between sunscreen brands. (14) Therefore, exogenous compounds not only could be used to indicate lifestyle preferences of a criminal suspect but could link evidence to a suspect based on brand identification. The presence of the three UVB blockers avobenzone, octocrylene, and octisalate indicated that this donor most likely wore or came into contact with sunscreen on the day(s) of residue sampling or close to then. Additional study on the persistence of these analytes in washed hands would be valuable to make additional conclusions. The high variability within samples from the same donor makes it challenging to set absolute quantitative cutoffs for forensic casework. The ability to resolve those compounds of interest in fingermark residue with ample chromatographic space for resolution of potential anthropogenic analytes of interest is a benefit of using a nontargeted analysis for a screening of forensic evidence, even with high variability between individual donors. The identification and presence of trace analytes that could link a suspect to a crime scene or crime are an important component of trace evidence analysis.

J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 10, 2299–2309: Figure 6. (A) Presence of UVB blockers found in three replicates of one fingermark donor. Replicate samples are grouped by colored blocks on the x-axis. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of five fingermark donors (n = 3). (C) Analytical ion current (AIC) of donor with cosmetic contamination. Cosmetic peaks: (1) diisopropyl adipate, (2) octisalate, (3) octocrylene, (4) avobenzone, and (5) α-tocopheryl acetate.

J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 10, 2299–2309: Figure 6. (A) Presence of UVB blockers found in three replicates of one fingermark donor. Replicate samples are grouped by colored blocks on the x-axis. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of five fingermark donors (n = 3). (C) Analytical ion current (AIC) of donor with cosmetic contamination. Cosmetic peaks: (1) diisopropyl adipate, (2) octisalate, (3) octocrylene, (4) avobenzone, and (5) α-tocopheryl acetate.

Conclusion

An initial comparison between 1D GC and GC×GC found GC×GC to be beneficial for fingermark analysis due to higher sensitivity and increased peak capacity for potential forensic investigations. A nontargeted method for GC×GC analysis was modified from the literature sources and optimized experimentally. Sample extraction of the fingermark samples from collection on microscope slides was evaluated for reproducibility. For consideration of more realistic forensic evidence, three finger sample depositions were compared with single finger depositions. Single finger depositions were found to be significantly lower in extracted peak areas but still produced a detectable signal. A LOD study based on fingermark analyte standards should be the focus of future work to determine qualitative threshold values that would be useful for forensic investigations.

Exogenous compound screenings could be useful in forensic investigations. Personal care products such as those found in this study could aid in lifestyle assessments of criminal suspects. In a nontargeted assessment of collected fingermark samples in this study, three sunscreen compounds and two moisturizer compounds were found in a study of six subjects; these were detected after the subjects had washed their hands and touched their face prior to deposition. Only one subject’s fingermarks contained UVB blockers found in sunscreens, and fingermarks from three subjects contained components commonly used in cosmetic moisturizers. These personal care product differences between individuals could be differentiated in fingermark samples using PCA to group subjects. Nontargeted screening of fingermark residues with an increased peak capacity has vast forensic implications. The extra chromatographic space provided by GC×GC combined with a nontargeted method optimized for fingermark analytes could provide a screening tool for routine forensic laboratories for lifestyle choices such as cosmetics but also for discovery of other forensically relevant compounds such as gunshot residue or illicit drugs that are present in fingermarks from touch chemistry. Further research on the analytical robustness and reliability of this method to analyze larger data sets with more donors and/or replicates would improve this nontargeted method.