Analysis of the Human Scent on Fired Cartridge Cases from a Simulated Crime Scene

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 7, 3799–3803: Graphical abstract

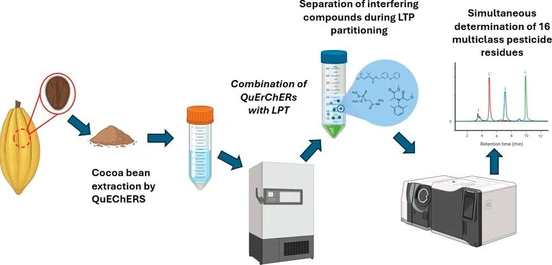

Fired cartridge cases are common evidence at shooting crime scenes. While fingerprints are often damaged and insufficient for identification, human scent traces may remain intact even after a gun is fired.

In this pilot study, a simulated crime scene was created in which a volunteer loaded a weapon before firing. The scent remaining on fired cartridge cases was analyzed and compared to reference samples from several volunteers using olfactronics and olfactorics. Results suggest that scent analysis can support investigations by linking cartridge cases to the individual who handled the ammunition.

The original article

Analysis of the Human Scent on Fired Cartridge Cases from a Simulated Crime Scene

Ulrika Malá*, Václav Vokálek, Pavel Vrbka, Jana Čechová, Petra Pojmanová, Oleksii Kaminskyi, Veronika Škeříková, Štěpán Urban

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 7, 3799–3803

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.4c06231

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

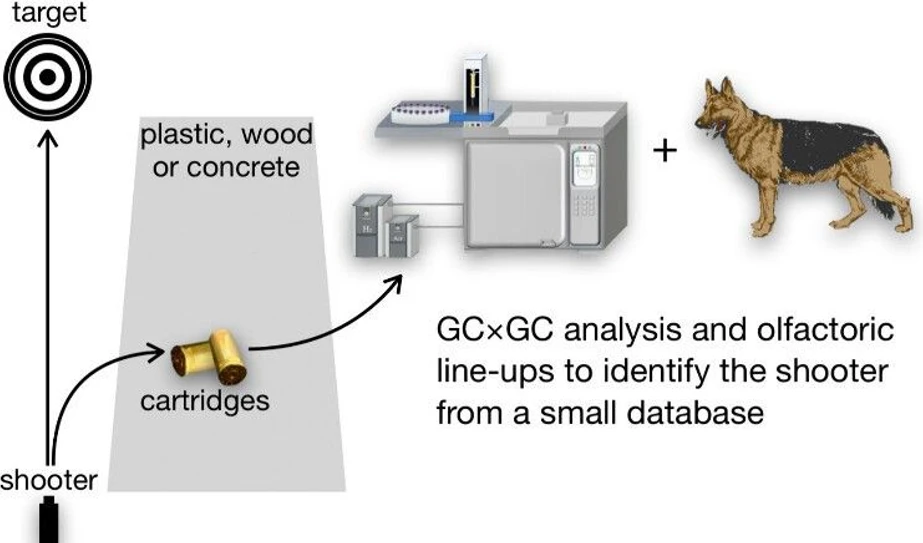

Forensic olfactronics is a new field of forensic analysis whose aim is to analyze scent samples using advanced analytical chemistry techniques. (1−3) Unlike olfactorics (the odorology method using specially trained canines), forensic olfactronics is an objective method. On the other hand, the olfactory system of a canine is still more sensitive than the best contemporary instruments of analytical chemistry usable for human scent analysis. This is why both methods should be used for these purposes in the future during criminal investigations, so they can complement each other and be a desirable chain of evidence to present before the court. Cartridge cases are often one of the traces that can appear on the crime scenes usually connected with a shooting, mainly in the cases of very serious crimes. Unfortunately, the fingerprints tend to be partially spoiled; thus, they cannot be compared with the dactyloscopy database. In a previous study, (4) it was found that the less volatile substances that seem to be more significant for the individual identification of human scent (5) resist high temperatures for a short time (up to 500 °C for 1 min). That led to a presumption that at least a part of the human scent remaining on the cartridge after loading the gun and even after the gun’s firing would be sufficient for an individual identification. (4)

Experimental Section

Instrumentation

For this experiment, only one gun type was used (a Sauer 38H, Sauer Sohn Germany, caliber 7.65 Browning, ammunition, type FMJ 73 grs, produced by Sellier Bellot, Czech Republic).

The samples were measured by a 7980B GC two-dimensional gas chromatograph (Agilent, USA) coupled with a Pegasus BT 4D time-of-flight analyzer mass spectrometer (LECO, USA). The columns were connected in reverse order. The primary column was a semipolar Rtx-200MS (30 m + 2 m precolumn, Restek, USA), and the secondary column was a nonpolar TG5-HT (1.1 m, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The diameter of the columns was 0.25 mm, and the thickness of the stationary phase was 0.25 μm. Helium (purity 5.5, Linde CZ) was used as a carrier gas for gas chromatography. The sample was injected in a volume of 1 μL in splitless mode (2 min) at a temperature of 280 °C. The temperature gradient on the primary column started at 40 °C, held for 2 min, and ended at 320 °C, held for 10 min. The temperature increased at a rate of 5 °C/min. The temperature on the secondary column was always 5 °C higher than that on the primary column. The modulator between the two columns always had a temperature 15 °C higher than the secondary column. The cryogenic modulation at −80 °C with three modulation periods of 6, 8, and 10 s were used. The carrier gas flow rate was 1.5 mL/min. The interface between GC and MS was heated to 280 °C. The mass detector used electron ionization with an energy of 70 eV ionizing electrons, and the temperature of the ion source was 250 °C. Data collection took place in TIC (total ion current) mode, with a mass interval of 29–800 (m/z); data collection took place at a speed of 200 spectra/s. The time required to elute the solvent was set to 500 s. To increase the detection sensitivity, a 200 V higher voltage was set on the detector compared to tuning. The ratio of the signal and the noise was set at S/N 300.

Results and Discussion

By comparing the chromatograms of the scent samples collected on the original and the prewashed cartridges, significant differences supporting the necessity of the cleaning procedure before the collection itself were not found. The chromatogram area where the lubricant peaks were found was more concentrated on the original cartridges, but the differences were not significant. From a practical point of view, that is efficient for our experiments, as it gets closer to reality at the crime scene. Other experiments were carried out on nonprewashed ammunition based on these results.

Our olfactronic analysis showed successful individual separation/variance between different volunteers on the glass beads (see Figure 3). However, the system could not link the human scent extracted from the gun-fired cartridge cases to the volunteers. This could have been caused by the different kinds of background material that was provided by glass beads (see Figure 1) and cartridge cases (see Figure 2), despite the fact that data editing was done in an attempt to eliminate these differences. Another option could be that even if the significant substances for the identification withstand high temperatures, the explosion heat could slightly change them. Therefore, one of the solutions could be to equalize the conditions before the extraction by heating the glass beads to the same temperature to which the bullets are exposed when fired. Nevertheless, the surface differences from which the unknown trace was collected at the crime scene do not seem to play a significant role. This is important for further investigation, as the cartridge cases remaining at the crime scene could lay on many kinds of surfaces, and the analyses of the evidence must not depend on them. The inconsistency of the result from the previous experiment (4) where the cartridge cases were successfully linked to the volunteer who had loaded the gun before the shooting could be based on the fact that another mass spectrometer (Pegasus BT-4D) with new commercial software (ChromaTOF, version 5.51.06.0) was used for this experiment. The software having issues with processing the chromatograms (mainly peak areas) may have contributed to the inconsistency.

![Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 7, 3799–3803: Figure 1. Chromatogram of a volunteer’s sample from our small database captured on the glass beads. The x axis represents the retention time of the first column [s], and the y axis represents the retention time of the second column [s]. The areas corresponding to individual groups of substances are indicated in the image.](https://gcms.labrulez.com/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/Anal_Chem_2025_97_7_3799_3803_Figure_1_Chromatogram_of_a_volunteer_s_sample_from_our_small_database_captured_on_the_glass_beads_f34c95896c_l.webp) Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 7, 3799–3803: Figure 1. Chromatogram of a volunteer’s sample from our small database captured on the glass beads. The x axis represents the retention time of the first column [s], and the y axis represents the retention time of the second column [s]. The areas corresponding to individual groups of substances are indicated in the image.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 7, 3799–3803: Figure 1. Chromatogram of a volunteer’s sample from our small database captured on the glass beads. The x axis represents the retention time of the first column [s], and the y axis represents the retention time of the second column [s]. The areas corresponding to individual groups of substances are indicated in the image.

![Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 7, 3799–3803: Figure 2. Chromatogram of an unknown sample from the cartridge case. The x axis represents the retention time of the first column [s]; the y axis represents the retention time of the second column [s]. The areas corresponding to individual groups of substances are indicated in the image.](https://gcms.labrulez.com/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/Anal_Chem_2025_97_7_3799_3803_Figure_2_Chromatogram_of_an_unknown_sample_from_the_cartridge_case_736c975356_l.webp) Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 7, 3799–3803: Figure 2. Chromatogram of an unknown sample from the cartridge case. The x axis represents the retention time of the first column [s]; the y axis represents the retention time of the second column [s]. The areas corresponding to individual groups of substances are indicated in the image.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 7, 3799–3803: Figure 2. Chromatogram of an unknown sample from the cartridge case. The x axis represents the retention time of the first column [s]; the y axis represents the retention time of the second column [s]. The areas corresponding to individual groups of substances are indicated in the image.

Conclusions

Two methods for comparing four scent traces from a simulated crime scene with 22 different volunteer scent samples were used. The aim was to find a certain volunteer who loaded the gun using eight analogous cartridges. Four samples of cartridge cases were then subjected to olfactronic analysis. These were collected from a heterogeneous crime scene. These four analogous samples were also compared by trained police canines. The olfactory method was successful and correctly identified the shooter. Both methods indicated that the surface (plastic sheet, wooden palette, and concrete floor) from which the scent traces were collected does not play a significant role in the identification. The results from the forensic olfactronic method showed the ability to distinguish each volunteer sampled on the glass beads; however, it has not yet been possible to link the fired cartridge cases to any of the volunteers. In the future, this problem can be eliminated by solving the problems with processing the peaks with commercial software that comes with the two-dimensional gas chromatograph. On the other hand, the issue could also be solved by equalizing the parameters on both surfaces (cartridge cases and glass beads) by heating the glass beads after the scent is collected on them. This heating would partly simulate the process of firing the gun.

Additionally, olfactronic identification could also be complemented by a dactyloscopy comparison as well. Since both can be crucial for the investigation and together can form a desirable chain of evidence. The only question is in which order should the methods be used for the optimal analysis of both.

The future prospects for the study include expanding the research to involve more volunteers and diversifying the types of weapons and ammunition tested. Additionally, further optimization of the sample preparation process is necessary, particularly to determine whether heating the glass beads to simulate gunfire can effectively link unknown samples to the shooter. Finally, addressing the issue of data alignment will be a critical step moving forward.